When and who….

The News and Courier 1873 article for Monday July 14, 1873, I began quoting in the introduction to this series on the church under my parking lot contains a sermon given by the pastor, Reverend W.C. Dana, where he documents the church’s history in four 12-½ year phases…and the reporter tells us the basics: date, name, denomination, and location of the church.

Central Presbyterian–The Semi-Centennial Anniversary Yesterday…

“Yesterday being the semi-centennial anniversary of the Third Presbyterian or Central Church of this city, the pastor, Rev. W. C. Dana preached a sermon appropriate to the occasion. (We will discover the name “Central” in the next post.)

“…Our Creator…had made this life a compound of mercy and judgment—of alternating good and evil. Our existence here is not one of unalloyed sunshine: It has its phases and eclipses. Churches like individuals have variations in their fortune. They experience their days of prosperity and their days of adversity. This church had in its turn experienced the vicissitudes common in a measure to others.

“On the 13th of July 1823, the Third Presbyterian Church of Charleston was organized. Of the male members then in union with the church (were) seven elders…–all now dead. A favorable opportunity for the purchase of the St. Andrew’s Church, in Archdale Street, presented itself, and it was purchased…. The congregation was soon increased by Christians…who cast their lot with the Third Presbyterian Church…On the 3rd December 1823, Rev. Wm. A. McDowell, a pastor of Morristown, N.J., received a call from this congregation….

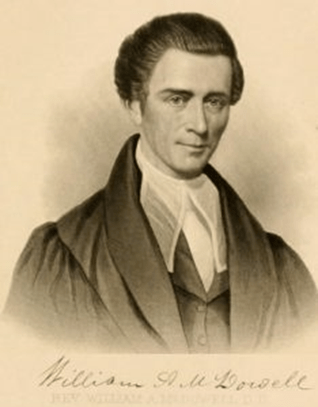

I need to pause the Reverend here for two things: First, the old Sanborn Fire Map I have shared in earlier posts showing the location of the church and the graveyard in 1884. It is on my block at the Archdale and West Streets corner. And two: that is all that Rev. Dana says about the first pastor of Third Presbyterian. So, I “googled” him. And the internet provided Rev. McDowell’s history and even a photo.

The Papers of William A. McDowell: A New Jersey Presbyterian in Charleston by Don C. Skemer

William A. McDowell (1780-1851) was a Presbyterian minister from New Jersey whose career was inextricably intertwined with the religious and civil life of Charleston during the 1820’s and 1830’s…

Born on the family estate in Lamington…NJ (he was graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) in 1809…”

During the next 14 years he studied theology and was a successful minister of a church for 9 years. Unfortunately, his health took a turn and when he received a call from Third Presbyterian Church in Charleston, it was decided that the milder weather would do him good. He and his new wife accepted the call and moved to Charleston in December 1823. “He remained there for a decade, much beloved by his congregation”….

Presbyterians in the Past William A. McDowell, 1789-1851 – Presbyterians of the Past, The Papers of William A. McDowell: A New Jersey Presbyterian in Charleston on JSTOR

The only local history source I found for the Third Presbyterian was in an online PDF book called the Illustrated Booklet of the Historic Churches of Charleston, South Carolina | David C Jones – Academia.edu. They said…

A splinter group from First Scots Presbyterian organized St. Andrew’s Presbyterian in 1814 and erected a building at Archdale and West streets. When the church disbanded nine years later, the building was sold to founding members of Third Presbyterian in 1823.

But the Illustrated Booklet doesn’t stop there…it goes off the rails a bit to mention two famous “founding members” that Reverend Dana did not get into his brief history…which, to be fair, was before his time…

Two of the Grimke sisters join Third Presbyterian Church

Angelina and Mary Grimké together joined Third Presbyterian in 1823… Angelina, the youngest of 14 children born to John and Mary Polly Smith Grimké, wealthy rice planters who owned many slaves, left Charleston at age 19 to join the abolitionist movement in 1824. With her older sister, Sarah, she went on a speaking tour of the Northeast for the American Anti-Slavery Society. Scandalized many by calling for an immediate end to slavery and, on top of that, making her case publicly before “promiscuous assemblies,” that is, audiences of both men and women.

Well…wow…And then, believe it or not…

Research Miracle #2

One of my favorite fiction authors is Sue Monk Kidd. After moving to Charleston, I found her book, The Invention of Wings written about the Grimké sisters of Charleston. It was published by Penguin Books in 2014 but I only heard of it when I began looking for books on Charleston after I moved here in 2020. Kidd’s book revolves around the Grimké sisters and abolition…and Reverend McDowell.

In her Author’s Notes Kidd goes into traveling here to research her subjects. She had lived here before. She was given complete access to the papers of the Grimké family including letters. And she freely says that sometimes you have to fudge a bit on the timing of things…to make a narrative story. So, Kidd’s date on the letters (1828) are off a bit from the dates from the Illustrated Booklet–December 1823, McDowell arrives–Nina becomes a member that same year–she leaves Charleston in 1824. There was time for them to have interacted…for a short time before she leaves town. Reverend McDowell, though, is just getting started and will still be at the church in 1828…Kidd’s date (below). A large part of historical research is trying to fill in the blanks and that is exactly why historical research is often subjective…

But if we stand back and take the 1000-foot view, a certain (subjective) scene comes into view. Here is Sue Monk Kidd’s take on the interchanged between Nina and Sarah Grimké regarding her time at the Third Presbyterian Church in her book The Invention of Wings. (page 285 and 294)

Letter from Angelina (Nina) to Sarah 16 February 1828

Dear Beloved sister,

You are the first and only to know: I’ve lost my heart to Reverend William McDowell of Third Presbyterian Church. He’s referred to in Charleston as the “young, handsome, minister from New Jersey.” He’s barely past thirty, and his face is like that of Apollo in the little painting that used to hang in your room. He came here from Morristown when his health forced him to seek a milder climate.

Oh, Sister, he has the strongest reservations about slavery!

Last summer, he enlisted me to teach the children in Sabbath School, a job I happily do each week. I once remarked on the evil of slavery during class and received a cautionary visit from Dr. McIntire, the superintendent, and you should’ve seen the way William came to my defense. Afterward, he advised me that when it comes to slavery, we must pray and wait. I’m no good at either.

He calls on me weekly, during which we have discussions about theology and church and the state of the world. He never departs without taking my hand and praying. I open my eyes and watch as he creases his brow and makes his eloquent pleas. If God has the slightest notion of how it feels to be enamored, he’ll forgive me.

I don’t yet know William’s intentions toward me, but I believe he reciprocates my own. Be happy for me. Yours, Nina

1 June 1828 Nina to Sarah

Dearest Sister,

…Some weeks ago, I went before a meeting at church and requested the elders give up their slaves and publicly denounce slavery. It was not well-received. Everyone, including Mother, our brother Thomas, and even Reverend McDowell, behaved as if I’d committed a crime. I asked them to give up a sin, not Christ and the Bible!!

Reverend McDowell agrees with me in spirit, but when I pressed him to preach publicly what he says to me in private, he refused. “Pray and wait,” he told me. “Pray and act,” I snapped. “Pray and speak!”

How could I marry someone who displays such cowardice?

I had no choice now but to leave his church. I’ve decided to follow in your steps and become a Quaker. I shudder to think of the gruesome dresses and the barren meetinghouse, but my course is set…Yours, Nina

Rev. McDowell was brand new to his post and fresh from the hallowed grounds of studying theology at prestigious schools and churches where abolition was being debated academically, and, one could guess, he was trying to adapt to what he saw when he arrived in Charleston: A smaller church barely inside the city limits where he was immediately confronted with a teenager of plantation wealth and privilege who felt she had a right to have her voice heard…and may have developed a short-lived crush on him. Each girl in her family was given their own personal body slave at a young age and Sarah, being the oldest girl could not abide it…leading her to the cause of abolition. Sarah first joined the Quakers on Meeting Street who were more liberal in a town that made its money on slavery…but was too adamant for them also and was asked to leave.

Nina will leave also, and the sisters will become leading lights in the abolitionist movement and will both marry years later. They also helped spearhead the push for women’s right to vote. They are celebrities in Charleston to this very day. Their home is a regular tourist stop and many websites and books tell their story.

Reverend McDowell did find his footing on the subject…whatever it turned out to be…and he and his wife will stay as a beloved pastor of Third Presbyterian for 10 years.

Rev. Dana in his semi-centennial speech brings the first phase to a close…

“The closing years of the first period were averse to the interests of the church. For several successive years the income was less than its expenses…In January 1, 1830, the committee said that besides the building debt the church was in debt one thousand dollars. During the presidency of Wm. A. Caldwell, he reported a debt of $4241, paid by subscriptions and pews. In 1833 Dr. McDowell received a call from the Board of Domestic Missions…we were compelled to part with him…”

Back to “Search” this time looking into attitudes about slavery in 1820-30s Charleston and hit upon

Research Miracle No. 3

Our Rev. McDowell, remember, had attended the College of New Jersey which later became Princeton. And don’t you know…there is a great article about the debate raging there for the same time period.

Princeton & Slavery | Presbyterians and Slavery

“…American Presbyterianism encompassed a wide range of viewpoints on slavery. Prominent leaders in the church were slaveholders, moderate antislavery advocates, and abolitionists.”

(Or to paraphrase in my words, Princeton came to the South and met aggressively pro-slavery Charleston where the debate was right in your face…and one learned to temper their statements regarding it being evil or a sin or you could be asked to leave. The time is twenty-six years before the Civil War. There was a long buildup to succession…with the topic becoming less and less academic…Reverend McDowell made it out just in time.

On July 29, 1835, pro-slavery residents of Charleston broke into a post office and burned all anti-slavery newspapers on the town square. The sign on the wall offers a ‘reward for Tappan’ referring to the brothers Arthur and Lewis Tappan, wealthy New York merchants who funded abolitionist activities. Fotosearch—Getty Images

Here are two concise non-political sites to view, if you chose to go further…

Slavery History In Charleston | Walks Of Charleston, The Tormented Rise of Abolition in 1830’s America | TIME

Also, here is an excerpt from the site of a local history treasure…Mark Jones. He has written many local history books, and he has a website “Today in Charleston History.” It is searchable! I sometimes share it on Facebook. This is what I found when I searched his site for “Grimke.”

Today In Charleston History: May 16 | MarkJonesBooks (mark-jones-books.com) https://mark-jones-books.com/2015/02/02/today-in-charleston-history, Mark Jones | Facebook

1838-Slavery.

Angelina Grimke Weld gave a lecture at Pennsylvania Hall to the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, a gathering of mixed-race abolitionists, amid a hostile atmosphere on the streets of Philadelphia, packs of mobs parading through the streets protesting the “amalgamation” of people inside the hall. (men and women)

As Angelina took the podium bricks and stones were thrown through the windows, with jeering from the outside easily carrying inside the hall, but she lectured for more than an hour, addressing the mob outside the hall:

What is a mob? What would the breaking of every window be? Any evidence that we are wrong or that slavery is a good and wholesome institution? What if that mob should now burst in upon us, break up our meeting and commit violence upon our persons – would this be anything compared with what the slaves endure?

This image of Sarah and Angelina Grimke Grimké are all over the internet and in books.

Sarah on the left, Angelina on the right

A book on Charleston that I love…A Short History of Charleston by Robert Rosen, University of South Carolina Press, 1997, has a quote from Angelina, also:

Angelina Grimké left her prominent family in Charleston to live up north. She was a leading spokeswoman for the abolitionist movement and early feminism. She wrote many pamphlets condemning slavery including one entitled “An Appeal to the Christian Woman of the South.” She told the Massachusetts legislature, “I stand before you as a southerner, exiled from the land of my birth by the sound of the lash and the piteous cry of the slave. I stand before you as a repentant slave holder.”

And perhaps, a writer of one of those papers being burned at the post office…

An Abolition Story from St. Charles, MO…

I will just call this a coincidence. When in St. Charles, I wrote a small book on St. Charles County History through a Woman’s Eyes. (St. Charles County Historical Society 2014) I included the story about a local abolitionist in the same year as the riot above…in 1835 Missouri…told from the viewpoint of his wife:

Celia Ann French Lovejoy—1835 Celia Ann, daughter of Sarah and Thomas French of St. Charles, was 22 when she married Elijah P. Lovejoy, a young Presbyterian minister in 1835. Their lives were changed forever when Elijah witnessed a black man being burned alive in St. Louis. He became an abolitionist and began to preach and write for his newspaper against slavery even though a law was passed making it illegal to do so. The couple were at her Uncle Millington’s house when a crowd attacked them. They were able to flee to Alton (Illinois…a free state), where they were attacked again, and Celia’s husband was shot 5 times. She was 24 with a new baby. She never remarried and moved out West. http://www.findagrave.