I have documented what little history that I could find in this blog of the church graveyard that was moved just before they paved the new city parking lot in my backyard and the church and congregation that went with it. I was very lucky to have the News & Courier articles to follow, especially the 1873 article that was of a sermon by the pastor of the church on their 50th anniversary.

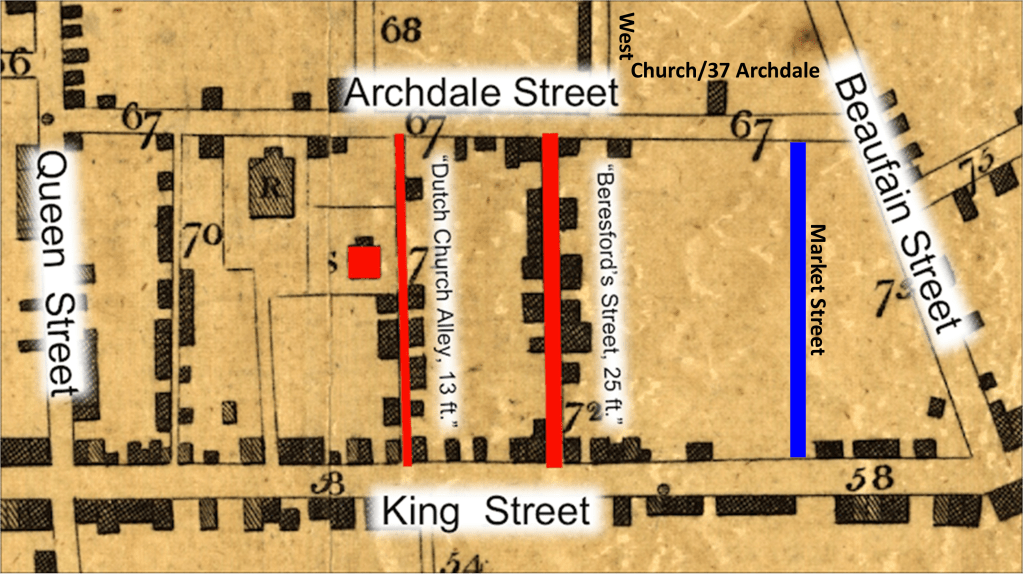

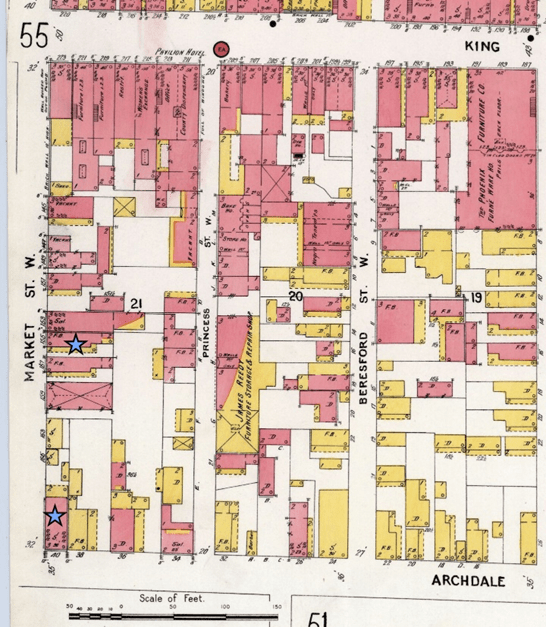

While the church started out on Archdale Street in the block between Market and West Streets (west side) in 1823 in a wood frame structure built in 1814, they moved to Meeting and Society Streets in 1850, building a Roman Temple style church for themselves and changing their name to Central Presbyterian in 1852. We tracked them in their new church through good times and bad until 1873, the date of the newspaper article…and the Illustrated Book of Charlston Churches.

Still a Mystery

But…a mystery remained…Why did the church move and abandon their first church in 1850, after it had survived the Decade of Fire? And why abandon their graveyard after two Civil War burials in 1865 and it was buried under a garbage dump until 1950 when the whole block was cleared for more city parking?

But in 1850, there were and still are two iconic 1700s churches already on Archdale Street, down a block and across the street from where Third Presbyterian had stood…St. John’s Lutheran and the Unitarian Church…and where my parking lot for Canterbury House is now. Also, a huge gothic Grace Church Cathedral…as big as it sounds…was nearing completion on Wentworth Street, a block in the other direction—the same year that Third Presbyterian left. So, it wasn’t that they were still lone rangers on the Archdale Street outer edge of downtown.

So, I went looking…

A Reason

And I found an answer–though there may be others. But unlike fire and war, this reason is about the destructive side of human nature.

Since the town is built on a narrow peninsula…moves away from something unpleasant or to something better was just a matter of a few blocks so it had to be a big reason. I’m going to give the bare bones here of what I found mostly showing how it affected my block…and the close neighborhood…and the church but also beyond it. Sources and links will be provided if you want to pursue it further…and there is more. While I try to study everything I can find on a subject, I tend to quote the sources with the clearest information packed into the fewest words…

The Holy City was also Sin City…exuberantly so.

“Before the outbreak of the Revolutionary war, city officials became concerned that the level of drinking and debauchery on the edge of the harbor would interfere with the protection of the city, ordering the prostitutes to move several blocks inland. The new red light district was resettled amongst the streets flanking St. John’s Lutheran and the Unitarian churches, an area known as Dutch Town settled primarily by Germans. During the British occupation of Charles Town, the area comprised of Beresford (now Fulton), Clifford, Magazine, West, Beaufain, Mazyck (now Logan) and Archdale Streets warmly welcomed soldiers with coats of any color.” Charleston’s Brothels (loislaneproperties.com)

A church caught in the middle…

This was not a passing phase. The brothels did not go away after the British occupation. Think about it. The reputation of the neighborhood could well be the reason that the St. Andrews group who built the wood structure on Archdale in 1814 moved. The price of land would have been low being on the very street that had town on one side and outskirts on the other…and Market Street that consistently had a bad reputation forever because of the wharfs and the market…that dead ended into Archdale right at my block. And may be why the St. Andrews group moved out again. And why Third Presbyterian Church moved in as a brand-new church. Reverend Dana’s remembrances of the first 25 years were dominated by money concerns, and they moved out as soon as they were financially able to buy land in a better location.

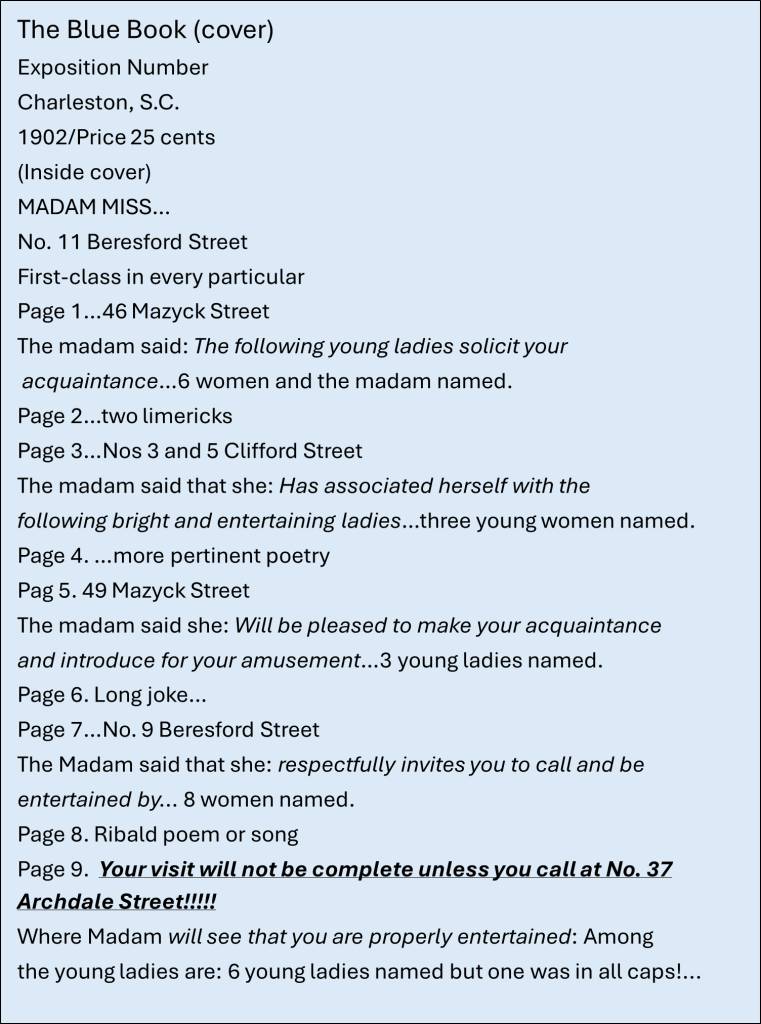

Mark Jones in Wicked Charleston, Volume 2 picks up the timeline with the story of Madam Grace Piexotto’s who built her world-famous bordello, known locally as The Big Brick, right across the street from Third Presbyterian at 11 Beresford Street…in 1852. She would have picked that street because it was the center of all the action…and centrally located in Charleston.

About a Decade later…

During the Civil War much of the town was empty (because of the constant bombardment) leaving mostly soldiers and women. There was a prohibition against liquor and a scarcity of liquor due to the siege of the city. Regular people had moved away or to the North Charleston area. Bordellos remained. Jones said “free colored street walkers and loose white women impudently accosted passersby”…. In February 1862, Colonel Johnson Hagood established military police to prohibit ‘all distillation and the sale of spirituous liquors.’ Because the rule was routinely ignored, often by the military police themselves, it was finally lifted, and the nightlife continued with the whorehouses, brothels and bordellos all doing booming business.” Mark Jones in Wicked Charleston, Volume 2

We don’t hear much about right after the Civil War but the lower peninsula and the main city looked like Gaza today…heavily shelled and burnt…with Archdale Street being the outer perimeter of the shells’ range fired from Ft. Moultrie across the Cooper River side of the peninsula. The shells mainly hit the town’s wharfs, churches, business and government centers clustered between Archdale and the river and south to the bay. Some of the old wooden houses in the Red-Light zone remained standing…as apparently did the old church…as residents trickled back into the city to rebuild their homes, businesses, and churches.

A New Century

By the turn of the century to the 1900s, the ladies who had stayed with the soldiers during the war had done quite well…became emboldened.

In 1901, a huge Exposition was held in Charleston and “hundreds of thousands” of visitors came to town. The ladies wanted to share in the wealth coming into the city, so they put out a book advertising their bordellos and naming the women at each place…though I chose not to include their names…because of family genealogy searches. You can get Mark Jones’ book if you want them.

However, one of those places listed was 37 Archdale Street, the old Third Presbyterian church.

“In 1912, many locals believed the availability of brothels was actually a good thing since it ‘protected the respectable ladies in the city’ from unwanted sexual attention. Prostitution was so readily available in Dutch Town that “on steamy afternoons Clifford Street so resounded with ribaldry flung from open window to open window by out-leaning women that shoppers on King Street stopped and looked” …The members of St. John’s Lutheran Church complained to the city about the mattress girls (girls walking the streets carrying a folded up mattresses on their backs!!!!) plying their trade along the front gates of the church (on Archdale.)

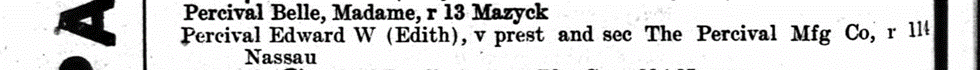

Some ladies even began advertising in the City Directories in the early 1900s.

And then…as we knew it would…something really bad happened in the neighborhood. Because of WWI, there was an increased military presence in the Charleston area.

The Charleston Riot of 1919 | Charleston County Public Library (ccpl.org)

“On leave, young sailors and soldiers from all over the United States, with a variety of backgrounds and attitudes, streamed into the city looking to unwind and have a good time. At the turn of the twentieth century, Charleston’s red-light district, euphemistically called the “segregated district” by the city government, encompassed a few urban blocks bounded by King Street to the east, Archdale Street to the west, Queen Street to the south, and Beaufain Street to the north. With the entry of the United States into the Great War in 1917, and the expected influx of soldiers and sailors into the area, however, the Federal government pressured Charleston’s City Council to break up the brothels and speakeasies in the “segregated district” and to provide more wholesome entertainment for servicemen. That work was mostly complete by 1919, but stories of the neighborhood’s racy reputation persisted among young men of a certain age.”

“On the evening of Saturday, May 10th, 1919, a series of incidents occurred that snowballed into a large-scale riot that overwhelmed the rule of law in downtown Charleston. The principal participants in this event were visiting U.S. Navy sailors, called “bluejackets” by the press, and local African American men…The trouble began sometime after seven o’clock on Saturday evening, May 10th, but the precise cause was never fully determined. In the immediate aftermath of the riot, the local newspapers reported several conflicting theories about its origin and noted that there were “various reports” in circulation. One story mentioned a “pool room fight” as the initial trigger, while another mentioned a sailor being unhappy about the illegal whisky he purchased from a black man. Others reported that they heard that a black man had shot a white sailor. Despite this convoluted mixture of hearsay and distorted facts, all of the contemporary sources agree that the disturbances commenced somewhere near the intersection of Beaufain Street and Charles (Archdale) Streets. (Archdale Street, of ancient origin, was renamed Charles Street in 1916, then renamed Archdale Street in 1927.)

The Navy’s official investigation concluded that the most likely cause of the riot was a random sidewalk encounter between two white sailors and a black male. Sixteen-year-old Roscoe Coleman of Ohio and eighteen-year-old Robert Morton of Texas, both on leave from the Charleston Naval Training Camp, passed an unidentified black man on a sidewalk near the intersection of Beaufain and Archdale Streets. Some sort of spontaneous incident then occurred. Most likely it was a case of the black male failing to step aside in deference to the white men, as had been customary in the past. One newspaper report identified that black male as Isaac (but actually Isaiah) Doctor, a twenty-two year-old laborer who lived with his parents nearby, at No. 155 Market Street. (My Canterbury building is 165 Market St.)

Isaiah will die of a gunshot wound…eight others were shot but survived…but it will be another twenty-two years before a serious effort was made to rehabilitate the neighborhood…and another war.

The Red Light District

Dutch Town | Charleston County Public Library (ccpl.org)

“The most notorious change in the neighborhood came in the early years of the twentieth century, when the short block of Beresford Street became known as the heart of Charleston’s red-light district. Everyone seemed to know that brothels and other houses of ill repute dominated the street, but the city did little to address the issues.

“At the turn of the twentieth century, Charleston’s red-light district, euphemistically called the “segregated district” by the city government, encompassed a few urban blocks bounded by King Street to the east, Archdale Street to the west, Queen Street to the south, and Beaufain Street to the north.”

Only after U.S. military leaders applied political pressure in 1941 did City Council finally evict vice and immorality from Beresford Street. In March of 1942 the remaining people who owned property along the street petitioned City Council for permission to change its name. Beresford Street was tainted by the past, they said, and they wanted a new name that would be free of social stigma. City Council agreed and started brainstorming about a new moniker for the street. Casting an eye around the Council Chambers in City Hall, a member sighted a plaster bust of Robert Fulton, of steamship fame, and suggested the name Fulton Street. After a brief debate, the motion was adopted, and that was the end of Richard Beresford’s legacy.”

Mark Jones continues as did the troubles in the neighborhood…

“In October 1942, the U.S. Army declared that the ‘city of Charleston is off limits for all personnel.’…In conjunction with military officials, Charleston police raided Market Street and arrested 626 prostitutes—346 white and 280 black… (nevertheless many remained.)

“By the 1950s, prostitution was segregated in Charleston for the first time in 280 years. Of the twenty-two houses on Market Street, only five catered to black men…. By 1960, most of the prostitution had been completely driven out of downtown to the north area, closer proximity to the naval base, where it thrives to this day.”

Wicked Charleston, Volume 2, Prostitutes, Politics and Prohibition by Mark R. Jones, The History Press, www.historypress.net, Charleston, London

There is only one or two more posts I am going to do on this blog, Finding My Charleston. I want to catch us up with the maps…and what happened to my block in the 1950s… where I began this series of posts on the Church and graveyard under my parking lot at Canterbury House and then look at what was going on with Archdale and Market, my corner, since the founding of the town until the first little St. Andrews building in 1814.